How To Make Ginger Tea For Its Bioactive Benefits

Ginger tea offers several advantages. Many individuals have questions about how to make ginger tea to optimise its benefits. Frequently asked questions include whether fresh or dried ginger is better and whether organic or conventional ginger should be used.

Moreover, questions about the appropriate amount of tea to consume and whether it can influence a thermogenic effect if taken frequently are important questions.

Key Points In This Article

This article provides an overview of ginger, including its key components, therapeutic properties, Ayurvedic use, related case studies, and insight into how to make ginger tea based on both traditional and modern scientific view points.

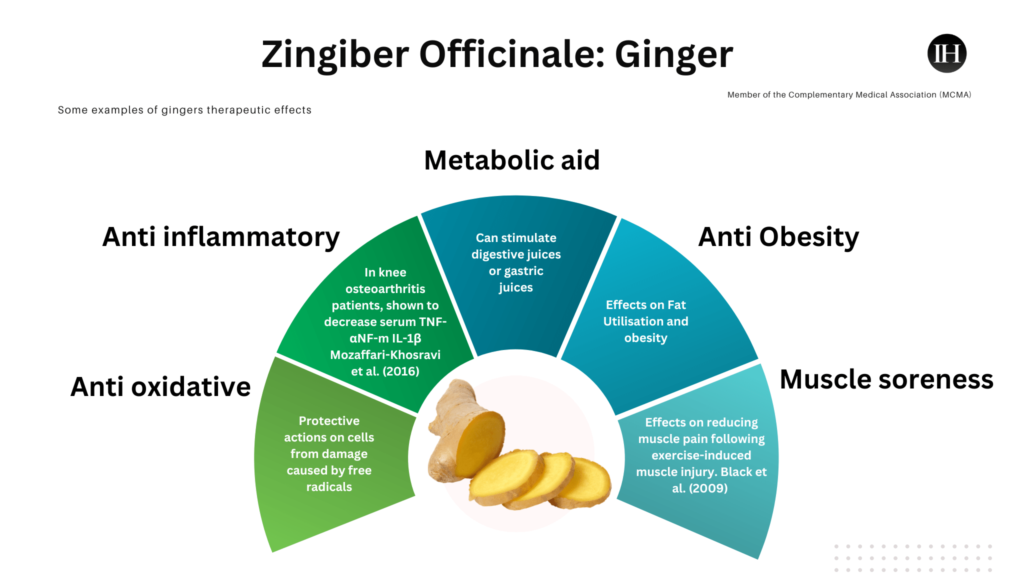

Zingiber Officinale: Ginger

For centuries, ginger has been therapeutic in alleviating gastrointestinal distress and reducing inflammation.

Interestingly, one of the reasons its properties are advantageous is that ginger and its metabolites accumulate in the gastrointestinal tract, as documented by Mao et al. (2019).

The botanical name for ginger is Zingiber officinale Roscoe, which belongs to the Zingiberaceae family of perennials.

The plant’s rhizome, commonly known as “the root,” is an important part used for its oily resin, “oleoresin.” This resin contains several vital bioactive compounds associated with pharmacological and therapeutic benefits.

Ginger has a long standing history with Asian cuisine and therapeutic use. Some of its associated actions include anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, gut management and general seasonal wellness.

Phytochemistry highlights an important bioactive constituent found in this plant, which is gingerol.

Gingers Physical & Aromatic Characteristics

The root of ginger is typically gold-beige and has a knobby, irregular shape. The outer layer is thin and easy to peel, revealing a fibrous, juicy flesh that is pale yellow.

The root has a distinctive spicy aroma and a hot, pungent taste due to the presence of gingerols and shogaols. Some individuals find its taste strong; however, it becomes gentler when taken as a tea.

Gingers Bioactive Compounds

Firstly, ginger is rich in gingerols, phenolics, and terpenes, each with unique actions.

Often, multiple compounds work together to produce specific therapeutic effects, known as a matrix effect in molecular sciences. This is vital to understand because it makes a difference to the overall value of the plant and its parts.

In essence, chemical reactions within components create particular effects, and often, the chain reaction interacts with body processes, thereby initiating particular effects.

For example, studies suggest that when gingerol interacts with a phenolic, it creates a unique capacity to reduce inflammation and relieve pain. Gingerols are responsible for ginger’s pungent taste and aroma, while other phenolics are known for their antioxidant properties.

| Gingerols | Phenolics | Terpenes |

Gingerols are also associated with being effective in reducing nausea and other important therapeutic actions. They are widely used in traditional medicine.

For example, according to Mao et al. (2019), there are many active constituents, including phenolic and terpene compounds in ginger root. The authors also report that gingerols are naturally occurring bioactive compounds found in fresh ginger. Some of the key highlights of the report are;

- The phenolic compounds in ginger are mainly gingerols, shogaols, and paradols.

- Among these, gingerols, such as 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, and 10-gingerol, are the primary polyphenols found in fresh roots.

- When treated in heat or stored for a long time, gingerols can be converted into corresponding shogaols. Shogaols is derived from Japanese, the word for ginger, and they too offer similar effects as gingerols.

- These compounds have been extensively studied for their therapeutic potential due to their potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

- It establishes that ginger effectively protects against oxidative stress, as observed by several studies.

Fresh Versus Dry Ginger: 115 Constituents

A variety of analytical processes have identified at least 115 constituents in both fresh and dried ginger varieties.

Fresh ginger contains gingerols as its major constituent, while dry ginger has slightly reduced concentrations of gingerols and higher concentrations of shogaols, the major gingerol dehydration products (Jolad et al. 2005).

Organic Ginger

There are several reasons why organic may be better for a diet than conventionally grown variety.

Here are three points to consider:

- Synthetic chemical free: Organic ginger is grown without harmful chemicals such as pesticides and fertilisers.

- Potential higher nutrient content: Organic ginger is grown in nutrient-rich soil, which may contain more effective compounds than chemically grown ginger.

- Better for the environment: as a result of organic farming promotes biodiversity, reduces pollution, and conserves water, making it a more sustainable option in the long run.

Nutritional Profile: Raw Ginger Root

The nutritional profile for 100 grams of raw ginger root, according to the United States Department of Agriculture are as follows:

- Energy, 333 kJ

- Protein, 1.82 g

- Carbohydrate, 17.8 g

- Calcium, 16 mg

- Magnesium, 43 mg

- Phosphorous, 34 mg

- Potassium, 425 mg

- Sodium, 13 mg

- Vitamin C, 5 mg

- Vitamin B-6, 0.16 mg

- Folate, 11 mg

- Choline, 28.8 mg

- Vitamin E, 0.26 mg

It also contains several other essential trace minerals in minor amounts, such as iron, copper, Manganese, selenium, Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Pantothenic acid, Vitamin K, Fatty acids, Tryptophan, Threonine, Isoleucine, Leucine, Lysine, Methionine, Cystine, Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, Valine, Arginine, Histidine, Alanine, Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid, Glycine, Proline, Serine and others.

Glycemic Index of Ginger Root

Ginger root is considered a low glycemic index food, with a glycemic index of approximately 15, according to glycemic index-net. This makes it a beneficial addition for those who want to include low-GI foods in their diet.

Pharmacological Properties of Ginger

In terms of gingers pharmacological properties the established and evidence-based links are vast in traditional science and modern-day studies. Some of these are detailed in the following sections in a limited manner.

Firstly, here are some therapeutic terms associated with ginger:

| Anti inflammatory | Anti oxidant | Anti Nausea | Anticarcinogenic Activities |

| Cardiovascular Preventive effects | Antidiabetic effects | Digestive support | Anti Allergy |

Examples of Ginger Case Studies

1. Anti-inflammatory Effect

According to the study “Ginger on Human Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of 109 Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients (Anh et al., 2020):

“Several randomised controlled trials have reported the anti-inflammatory effects of ginger supplementation.”

The majority of these studies focused on arthritis-related diseases, especially osteoarthritis. Six studies that investigated the efficiency of ginger constituents as anti-inflammatory agents for osteoarthritis all reported improvement in patients who consumed ginger compared to the control group.

For example, Mozaffari-Khosravi et al. found that after three months of consuming 500 mg of ginger powder, the level of proinflammatory cytokines was reduced, leading to patient benefits. Ginger also showed promising results in relieving pain in osteoarthritis patients.

Ginger Suitability

Additionally, no significant adverse effects were observed during the trials.

Lastly, Kulkarni et al. found that ginger supplementation alone and combined with antitubercular treatment significantly decreased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, ferritin, and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels compared to the control group.

[The details of these studies can be found at the end of this article in the references section: (Anh et al., 2020)]

2. Metabolic Effects

Anh et al. (2020) conducted a comprehensive systematic review of 109 randomised controlled trials on ginger’s impact on human health. Several studies assessed the association of ginger supplementation with metabolic syndromes, including type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity.

The studies demonstrated significant benefits of ginger intake in reducing fasting blood sugar, hemoglobin A1c, insulin sensitivity, insulin resistance, C-reactive protein, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and malondialdehyde.

Ginger was also shown to have positive effects on insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance and on the increase of quantitative insulin sensitivity check index in obese women.

Additionally, ginger was believed to provide potential benefits in reducing the risk factors of metabolic syndromes, such as body fat mass, body fat percentage, total cholesterol, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and insulin resistance. No serious adverse effects were observed in all included studies.

Ayurvedic Principles

Ginger is an essential Ayurvedic medicine therapeutic known to have properties helpful in several areas already discussed.

The root effectively balances the Vata and Kapha elements, especially when disturbed. The root combined with jaggery is often used when dealing with Vata issues such as colds and coughs, seasonal stress caused by colder climates, or inner tendencies.

Ginger is also known to help optimise digestive fire or “Agni,” which is an individual’s natural and optimal metabolic capacity.

Exaggerates Heat (Pitta)

However, pitta tendencies can be further aggravated and induce more internal heat, and in such instances, ginger would not be suitable.

Moreover, some individuals may not be well-suited to it due to its spicy (hot) sensation. Studies suggest ginger may aggravate gastro symptoms, heartburn, bloating, etc. This co-relates to the pitta tendency in certain individuals in relation to ginger use and is recognised by Ayurveda.

How To Make Ginger Tea

We have emphasised in many of our articles the significance of using natural sources, especially when it comes to dietary therapeutics.

It is essential to consider the source of any therapeutic carefully as it is subject to a food matrix effect and interaction with body processes. These factors can influence their overall efficacy.

Once the source is selected, ginger tea can be made from either fresh root/stem or dry powdered root/stem.

To know more about different preparation methods for phytotherapeutic tea read here.

1. Ginger Tea from Raw Fresh Root

Tea from fresh, raw root contains water content, i.e., the juice or water in the plant. To some extent, this water content varies in compounds which can be more or less depending on the plant.

In Ayurveda, raw ginger root is considered a good source of its compounds but it has to be diluted before consumption.

Tea from raw, fresh root can be made as follows;

Boiling, maceration or steeping are used to make ginger root tea in Ayurveda.

- For example, 2-3 large slices or 4-5 small pieces of ginger for a single cup (240-350ml) can be used. The pieces can be sliced, grated, or beaten using mortar and pestle to activate aroma and its bioactivity. This is used whole, juice and pulp in water, depending on the method of brewing.

- Alternatively, 10-15 ml of fresh ginger juice can be added to hot water.

- Ginger skin can be peeled before use, but it is also used skin included in several traditional practices.

- Once ready, this is then strained before consuming. Natural sweetener such as honey can be added before consuming. Ginger tea is taken in moderation once a day or alternative days depending on suitability or as advised.

Consideration: according to Easyayurveda, fresh wet ginger can be Vata aggravating due to its drying effects when consumed; adding jaggery can balance this effect.

2. Ginger Tea from Dry Powder Root

Dried ginger powder is made from ground dried ginger roots making a fine powder.

It has a pungent and spicy flavour and a distinct taste and aroma. This form of root does not contain water content as it is dried.

Subsequently, the bioactivity of dry powder will vary compared to its wet raw state. However, sun-dried powder is a significant component in several traditional therapeutics, such as Ayurveda.

Tea from dry powder can be made as follows;

- Approximately a level quarter teaspoon of dry powder is added to water for a single cup, 240-350ml.

- This is then infused or boiled; in the case of dry powder, it tends to be slightly stronger. The strength of the powder can vary and depends on the quality of production, origin, and processing. The quantity can be adjusted as preferred, i.e. less than a quarter-level teaspoon.

Accounting for Preparation Methods & Impact On Constituents

Tea can be prepared by either infusing or boiling the chosen root.

Once the tea is prepared, it can be sipped warm or at room temperature. Organic honey or jaggery can be added for taste and other benefits.

Other Variables To Consider

- Frequency: typically the tea can be taken once a day or on alternative days for a healthy adult.

- Ginger is considered a metabolic booster, as a result it may encourage internal heat. Therefore, ginger tea is avoided in hot summers unless for a particular therapeutic purpose.

- Dose: for support from seasonal cold and flu, 1-2 cups a day, depending on suitability. Alternatively, for a healthy adult, one cup, 3-5 times per week, as part of a well-balanced routine. Adjust as required.

- Time: GT can be taken anytime between sunrise and sunset in between meals as a rejuvenating tonic. Suitability depends on individual requirements.

Thermogenic Property

In traditional medicine, ginger is a heating food as it can influence metabolic processes.

This means when ingested and digested, it can generate heat within the body. However, it depends on several other factors, such as frequency, standalone or other ingredients, Ayurvedic Prakriti, etc.

Cold Climates

Subsequently, dry powder or fresh root may be suitable for seasonal tea tonic.

This is due to its pitta-enhancing (thermogenic) properties, i.e., internal heat. Ginger tea is an exceptional dietary therapeutic for seasonal colds and flu because gingerol has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

Summary

This article discusses the benefits of ginger tea and answers common questions about making it.

It explains ginger’s key components and therapeutic properties, including its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, gut aid, and general seasonal wellness effects.

It also highlights how to make ginger tea with fresh or dried ginger and the appropriate amount to consume. The article also covers the suitability of organic ginger, the nutritional profile of raw ginger root, and its low glycemic index.

Additionally, it summarises examples of ginger case studies related to anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects. Lastly, it provides insight into Ayurvedic principles and how to make ginger tea from raw fresh and dry powder roots.

Suitability & Precautions

While ginger is generally generally safe, suitability depends on individual factors. Precautions and personal responsibility are crucial. Check suitability for pregnant, allergic persons and individuals with chronic health concerns, including pitta-dominant individuals. Seek the advice of a professional.

This post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional advice.

Informational Video: Ginger & Its Therapeutic Properties

References in this article

Mao QQ, Xu XY, Cao SY, Gan RY, Corke H, Beta T, Li HB. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods. 2019 May 30;8(6):185. doi: 10.3390/foods8060185. PMID: 31151279; PMCID: PMC6616534.

Bode AM, Dong Z. The Amazing and Mighty Ginger. In: Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, editors. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2011. Chapter 7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92775/

United States Department of Agriculture: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/169231/nutrients

Easy Ayurveda: https://www.easyayurveda.com/2014/12/20/ginger-benefits-research-home-remedies-side-effects/#medicinal_properties

Jolad, Shivanand D et al. “Commercially processed dry ginger (Zingiber officinale): composition and effects on LPS-stimulated PGE2 production.” Phytochemistry vol. 66,13 (2005): 1614-35. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.007

Anh NH, Kim SJ, Long NP, Min JE, Yoon YC, Lee EG, Kim M, Kim TJ, Yang YY, Son EY, Yoon SJ, Diem NC, Kim HM, Kwon SW. Ginger on Human Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of 109 Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2020 Jan 6;12(1):157. doi: 10.3390/nu12010157. PMID: 31935866; PMCID: PMC7019938.

Semwal, Ruchi Badoni et al. “Gingerols and shogaols: Important nutraceutical principles from ginger.” Phytochemistry vol. 117 (2015): 554-568. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.07.012